Concept

Recently, I came across the existence of this technology that, to me, approximates magic; needless to say, I had to dive right into it. I’ll steal the definition right from Wikipedia:

Microbial fuel cell (MFC) is a type of bioelectrochemical fuel cell system that generates electric current by diverting electrons produced from the microbial oxidation of reduced compounds (also known as fuel or electron donor) on the anode to high-energy oxidized compounds such as oxygen (also known as oxidizing agent or electron acceptor) on the cathode through an external electrical circuit.

Simply put, one can harvest the electrons that some microorganisms release in their metabolism by collecting them with one electrode and let them flow towards a second electrode that will accept them in some way. This flow of electrons is, by all means, an electric current.

Approach

Since I know nothing about organic chemistry, I tried to collect information online on existing experiments or random DIY solutions to understand if there was anything near my level of knowledge that could allow me to reach my goal: to light up at least an LED for some seconds. As a matter of fact, a very simple solution exists: common soil typically contains two electrogenic species of bacteria (Shewanella putrefaciens and Aeromonas hydrophil) that can transfer electrons to the anode directly with their pili and membranes without the need of any chemical mediation.

First Experiment

With very little hope in my understanding of the subject, I decided to put together a first test. I dug up some dirt to mix with water and crafted two very simple electrodes with a spiral of copper wire.

I put the first spiral on the bottom of a glass jar, covered it in mud, and put the second spiral on top. The bacteria I mentioned have a peculiarity: they are facultative anaerobes, which means that their metabolism can be both aerobic (reduce oxygen) or anaerobic (donate electrons to other oxidizers). Theoretically then, the absence of oxygen in the bottom of the jar makes the bacteria change their metabolism to anaerobic and donate electrons to the metallic anode. Here, electrons flow through an electric circuit up to the cathode, where an electron-acceptor (i.e. oxygen) is reduced.

Again, with very little hope, I hooked up a multimeter to the electrodes and:

2 millivolts! The amount of energy was obviously incredibly small, but still it worked on first try!

Second Experiment

At that point I was planning on building a number of other cells and gradually change different variables to understand what would impact their efficiency the most. The factors I was most interested in testing where the surface area of the anode and its minimum depth. By maximizing the first I thought I could maximize the collection of electrons for the same amount of soil, while by minimizing the second I was looking for the most compact design possible, so as to put several cells in series or parallel in the same space. The problem with the second factor I thought would be the permeability of the soil, meaning that if oxygen transpired through the thin layer of dirt, the anode wouldn’t be in an anaerobic environment anymore and not work.

Anode dimensions turned out to be a huge game-changer: replacing the copper spiral with an aluminum surface folded accordion-like, the same amount of soil yielded up to 800 mV compared to the previous 2 mV! Here’s a picture of the bottom electrode, which was later covered with more mud and topped with the same cathode as before:

Third Experiment

What was left at this point was trying to put a bunch of cells in series and create a high enough voltage to be stored and used to power something, maybe even just an LED to reach my initial goal. I admit I had little hope, given the incredibly small current that the cells could output (my multimeter has a resolution of - it says - 0.1 uA, and couldn’t read anything).

I grabbed a plastic box and the bottom of some water bottles to form an array of small containers, and crafted another 8 large anodes with aluminum foil just like the previous one.

After creating the first half of the array, the output was already satisfying: 2.7 volts!

At this point I was wondering if paralleling the two halves could have been a better choice than a single series connection, given that all in all the voltage was usable. On second thought though, I considered that in the previous days I observed the output voltages to be somewhat unstable and often different from cell to cell, which would cause the two half-arrays to have different tensions and therefore not work optimally.

I completed the array and got a bit over 4 volts. Time to hook up some capacitors and an LED!

As I said though, the output is pretty unstable and (generally) increases over time, probably while the oxygen gradient settles in the soil and possibly other biochemical conditions I’m not aware of. At first, in fact, I used a very large capacitor (18.000 uF), but at ~1.35V it would stop charging because the leaking current was greater that what the battery could output, and had to swap it for two smaller 2.200 uF caps. Three days later instead, the output voltage had risen from 4.5 volts to more than 6, and the big capacitor could now charge just fine in a couple of minutes.

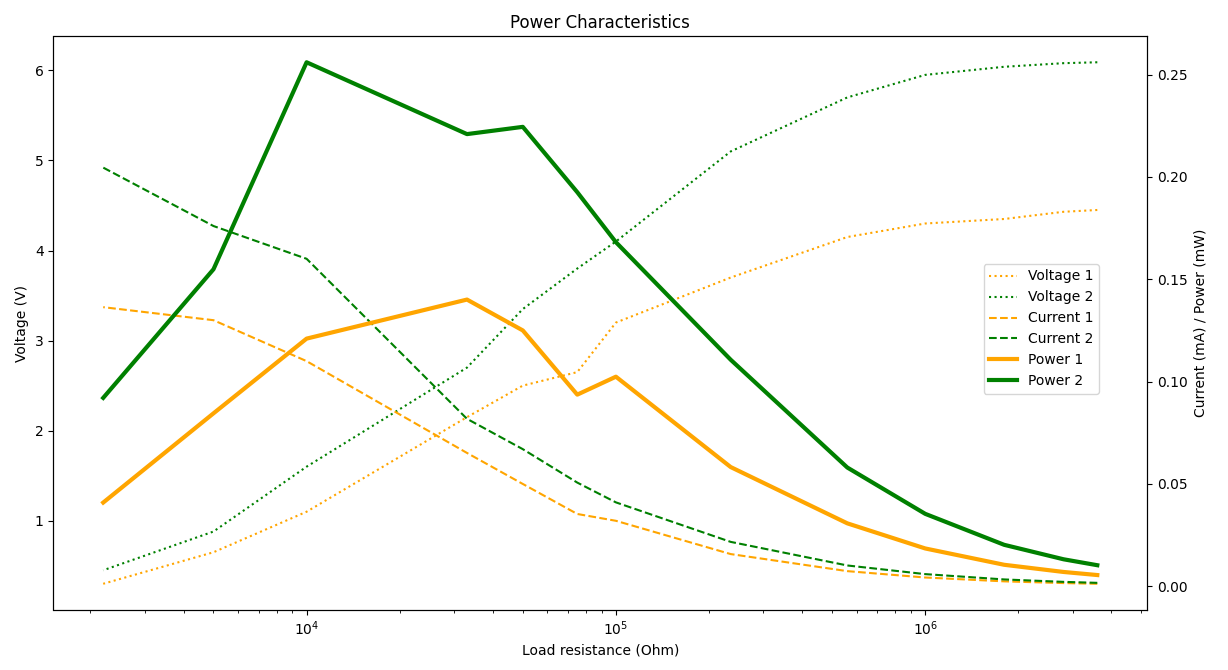

For show, here’s a comparison of the output characteristics of the battery between day 1 and day 4:

What to say… It still looks quite unbelievable to see several hundred micro-watts come out from literal mud.